In this article, I will analyze the Porter’s Five Forces

affecting smaller generic pharmaceutical companies, using the example of

Lannett (NYSE: LCI), which have annual revenues of $400mm ~ $1,000mm.

(Photo Source:

Internet)

Key Takeaways:

- Small/middle- sized generic pharmaceuticals face strong bargaining

power from buyers, potentially squeezing their margins

- Current regulation regime keeps generic pharmaceutical

players in an upward trends; it’s safe to project 5-year cash flows

- Sustainable and decent margin, as least in the short-run

OK, let's begin.

First, get some big picture from IBIS world:

“The $61.0 billion Generic Pharmaceutical Manufacturing industry is

expanding rapidly, with annualized revenue growth of 4.5% expected in the five years to 2015. An aging population with more chronic illnesses is driving demand for

industry products, while regulatory provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act expand consumer access

to prescription insurance and provide increased opportunities for product

development. Industry revenue is expected to grow 3.7% in 2015.”

Sounds good. From this

10,000 feet view, we can place LCI as a middle-size player that has grown from $106.8

million revenue in 2011, to $800+ million revenue in 2016 after the Kremers

Urban acquisition.

What’re the forces

driving LCI’s growth? Let’s start with Porter’s Five Forces.

#1) Threat of new

entrants

Although generic companies manufactures lack patent

protections like brand-name drug companies, they still enjoy decent ~10% Net

Margins. Logically, there should be some barriers, such as followed:

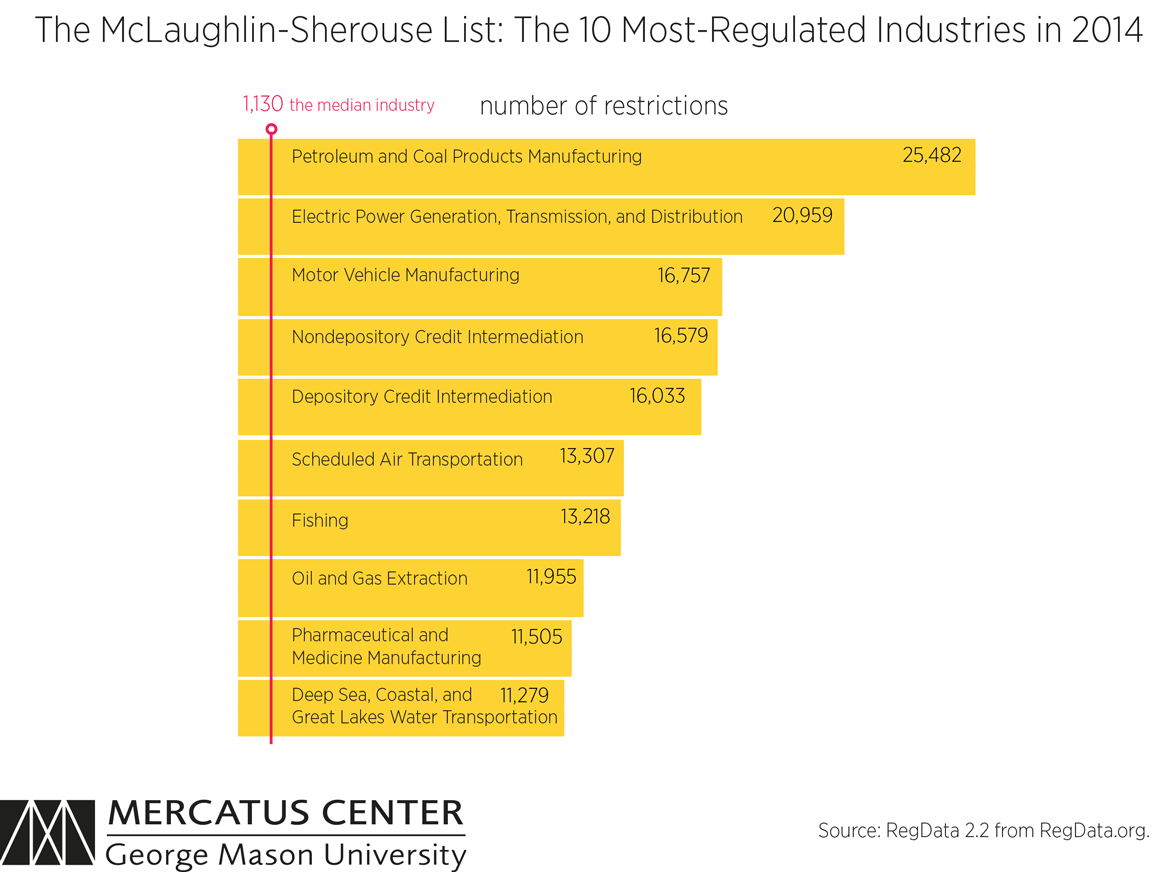

- Regulation: The

production of generics is strictly regulated and companies must adhere to

stringent goods manufacturing practices and quality-control standards from FDA.

- Cost of production

facilities: in US, there’s an interesting “frame of tenders”. It obliges

pharmacists to dispense a discounted generic product if one is available. Under

this scheme, health insurers are able to pressure prices and request a high quality.

This requires companies to be able to quickly produce high volumes and at a low

manufacturing cost, and high quality. So small players are difficult to get

foot in the door.

#2) Bargaining power

of buyers

Let’s first look at a simplified supply chain of

pharmaceutical industry:

- Strong

counterparties: As a manufacture, LCI’s clients are strong and consolidated

wholesalers. Today, the top three wholesalers own 90% of the market share.

Their revenue model has evolved into a low margin business that makes money by

maximizing economies of scale, creating physical distribution efficiencies and

financial efficiencies (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005).

That’s bad, if you have strong counter-parties. That being said, in an environment that retail price is increasing, will wholesalers keep

a fixed markup, or ask for a high margin? I will write about this in another

article.

- Brand recognition:

for generic products, brand seems useless. The pharmacist can provide any generic drug, as long as it has the

effective content.

#3) Bargaining power

of suppliers

- Low bargaining power

from suppliers – the upstream is commoditized, reflected by low COGS (~20% of revenues)

However, we should keep in mind generic pharmaceutical companies can be manufactures, as well as distributors.

For instance, LCI's over 50% revenue comes from one single supplier, JSP. It is because that LCI is acting as a distributor, not a manufacture in this case.

#4) Threat of substitute

of products or services

That’s a tricky question, and Game Theory is in play

- There’s a certain cost to produce a generic drug, such as

FDA and facility cost

- However, the revenue side is uncertain, depending on

numbers of players in the market

For instance,

assuming a drug demand is $100 million, and the brand drug is priced at $100; fixed

cost to launch this drug is $10million and COGS is 20%. We can play following scenarios:

(In $ Millions)

We can find that the third player will not enter the market,

leaving existing two players enjoying higher drug price and margins. In another words, after a certain threshold, new

competitors don’t have an incentive to launch a drug and existing players can

enjoy less rivalry.

#5) Rivalry among

existing competitors

It’s also a product by product question. Similar dynamics

as described in the Threat of substitute

of products or services are also in play.

#6) Landscape

migration

It’s a big question, which needs another 10,000+ words to explain.

From the bird view, we should bear in mind that prospers of the generic

pharmaceutical market has come from one

act: Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984.

Since this Act, the industry has seen an increase in the

percent of branded drugs that have a generic competitor on the market. In 1999,

nearly 100% of the top-selling drugs with expired patents had generic

versions available, versus only 36% in 1983.

Is there a possibility that a new act will be in place and

completely destroy the generic pharmaceutical market? The short answer is definitely

YES.

Pulling data from Congress.gov, we found it takes average 267.57

days to pass a bill into law. But how long it takes to introducing a bill? The timeframe

varies from 2 weeks to forever.

For now, we can safely say (99% confident interval:)) that generic

pharmaceutical companies will keep flat/slight upward pricing in 5 years.

Based on this article, I will take a deeper look on

the recent client loss of Kremers Urban, now a subsidiary of LCI. Stay tuned :)

Related articles: